In my 20+ years in the material handling industry, I’ve noticed our salespeople tend to speak a similar language. I

frequently partner with sales as their technical expert for initial customer meetings and often hear a common theme in their preparation. Things like: "This will be easy," "There are several sites that will all be cookie-cutter," or my favorite: "We just need to give them the standard solution."But as we go through the discovery and design process from a technical perspective, we find that the "standard solution" only meets about 50% of the project needs, and the "cookies" look nothing alike.

So, what is a "standard" solution, and why does it never seem to satisfy without significant changes to either the solution or the business? Does it have to be the same thing every time? Does "standard solution" mean I can only have snowflake cookies? (Sugar cookie dough shaped like snowflakes shall henceforth be the standard cookie!) What if I promise to use sugar cookie dough - but I want a star or a tree - is that possible? Maybe the "standard" can be the star, the tree, and the snowflake.

Over the last 15+ years as a solution designer for material handling systems, I have talked and worked with people (often managers and executives) who push or demand that we "standardize" a particular offering. If "the standard design" can send high volumes of replenishment products to a store, it shouldn't be a problem to ship that same volume directly to customers when my stores suddenly close due to pandemic restrictions, right?

That's as far as many people look — shipping product = shipping product — but let's go back to the cookie analogy. You can certainly use different cutter shapes to make sleighs (big stores), snowflakes (medium stores), or stars (small stores) from the same sugar cookie dough. Add colored sprinkles at the end (locations across the country), and you achieve good results with only a few extra tools. But you won't be able to satisfy gingerbread (e-com), peanut butter (wholesale), or chocolate chip (discounters) requests by merely changing the shape of the cutter.

What's frequently overlooked when talking about standard solutions are the intricate details that define different operations. Within a retail replenishment inventory, a random mispick might elicit a few sternly worded emails and uncomfortable meetings. The root cause could be a mis-divert on a sorter, a replenishment to the wrong pick face, or a picker grabbing from the wrong slot. But well-managed organizations know the problem is likely a limited issue. The needed items will go out with the next delivery, and the mis-pick can be sold wherever it landed. It's a learning moment for the DC, but no real financial harm was done, and the response to "fix" the problem should be proportionate to the damage caused.

In contrast, if that same system mispicks direct to a consumer, it means a college student (we’ll call him “Tim”) gets a bottle of pink glitter glue instead of a fancy non-conductive glove for touch screen tablets. The root cause could be a mis-divert on a sorter, a replenishment to the wrong pick face, or a picker grabbing from the wrong slot (sound familiar?). Tim then calls, complains, and receives a promise to send him the correct product. As for the cost of the glitter glue and the wasted shipment – just keep it. The promise is eventually fulfilled with a new shipment several days later. We might still have a few sternly worded internal emails or uncomfortable meetings, but problem solved.

In the meantime, though, Tim left a poor review about his experience for the public to see. When laughing with his peers about the pink glitter glue, they'll talk about "the idiots" at company A sending out glue instead of a glove and conclude that a competitor will be the better choice for tech items from now on. And as a computer engineering major, his tech opinion carries significant weight with his friends. Problem still solved with the "standard solution?" Or do I now need multiple "standards" depending on how we are shipping? Maybe standards just don’t work.

But as we look at the world outside of material handling, are we missing the boat with standardization vs. standard solutions? For example, the arrival of the USB standard meant you no longer had to be a "nerd" to know how to plug a computer system together. Before that, learning the keyboard vs. mouse connectors — with serial, parallel, 9-pin, 25-pin, audio in/out — was one creative way to achieve near-deity status. But if you also knew how to install the right drivers – wow! That was beyond deity. Now, anyone can connect any device; it just plugs right in (with about three tries at most) and starts working. It is a standardized interface.

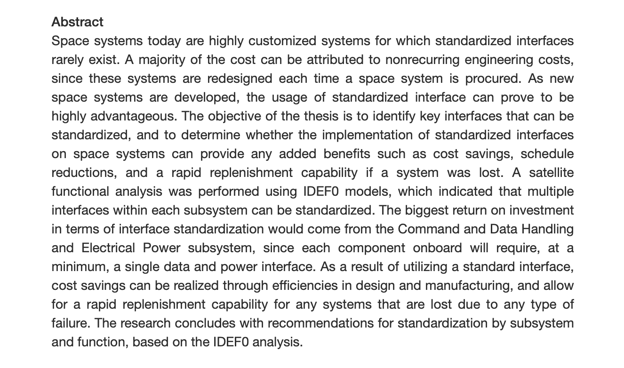

I recently came across a 2015 Master's thesis by Jonathan Lee, who studied the benefits of standardization for space systems. Instant cool, but then I thought: wait, aren't space systems already standardized? Surely joint missions to Mars, thousands of satellites, human and robot trips to the moon, reusable rockets, and hundreds of PhDs in the field have standards? Reading further, I realized this was not the case at all.

[Source: https://calhoun.nps.edu/handle/10945/47294]

In the passage above, replacing "space systems" in the first paragraph with the phrase "material handling systems" will effectively describe the state of many material handling systems today, as well as the approach of the whole material handling industry.

Almost everything we do in material handling is highly customized without standard interfaces. Many times, especially for large jobs, we start with a clean sheet of paper, then design the same tasks and functions over and over with each client and with new interfaces each time. Looking at the impacts in the case of the mis-pick above makes us believe we are justified in our approach. Designers will typically borrow heavily from previous designs, but "borrowing" is frequently limited by the designer's experience and restricts us from embracing new technology.

As Jonathan Lee demonstrated, if you take a step back and analyze methodically, you'll find that even for the wide variety of science and other new technology payload packages that go to space, commonalities like power and communications are required for all space-based payloads. Standardizing just those "simple" interfaces shows great promise for efficiencies and improved flexibility when things change. We don't have to "standardize" the payload, but standardizing the interfaces makes a world of difference.

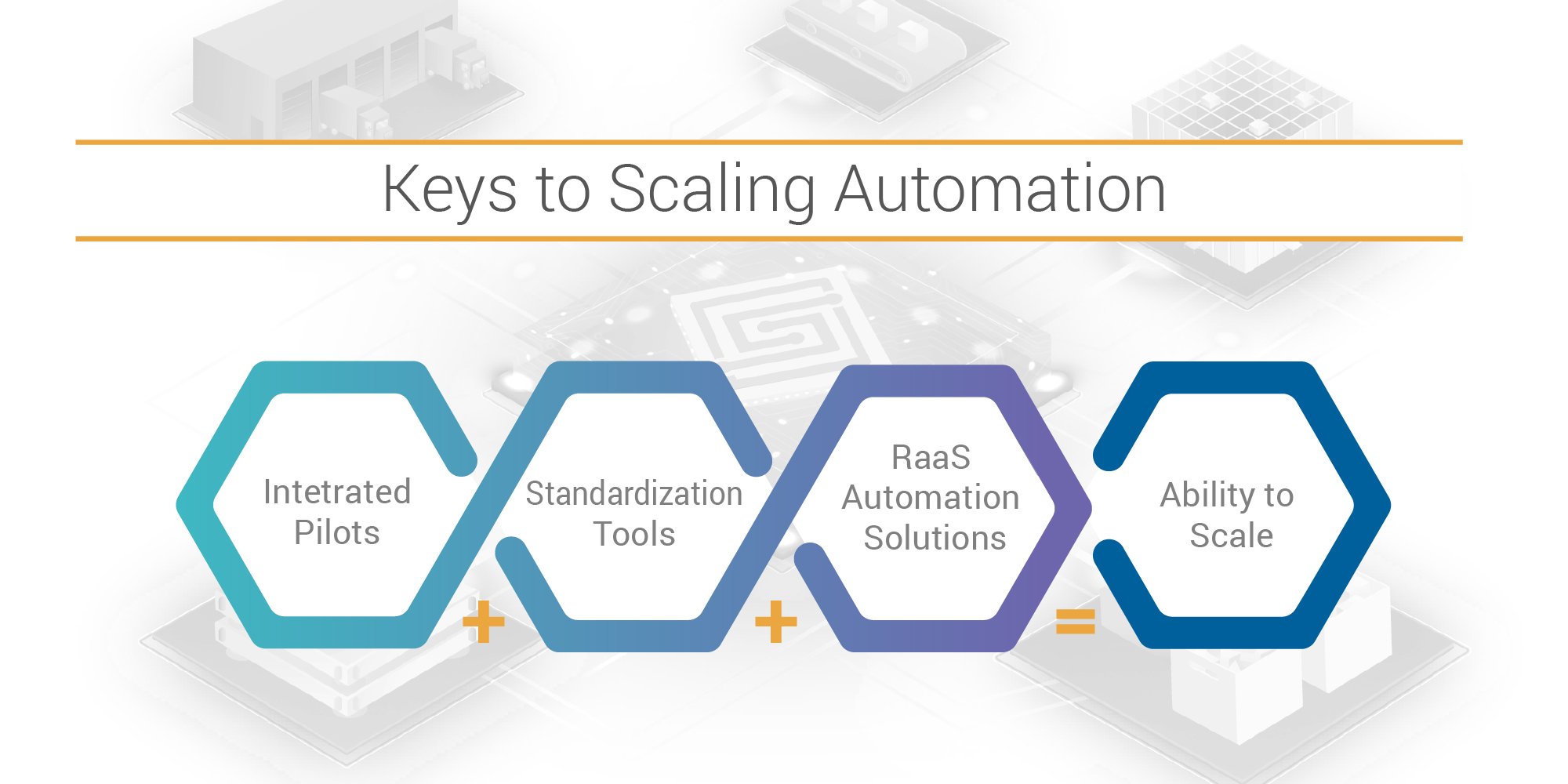

While not performing a formalized functional analysis with IDEF0 models for a thesis, SVT Robotics has identified several base commonalities where the material handling industry can enjoy some high-value standardization. These are not standard designs – meaning workflow and equipment – but they are standard interfaces that can work across all equipment and adapt to all workflows. No, SVT can't change chocolate chip cookies into sugar cookies, but accessing these base ingredients of flour, sugar, or eggs allows you to pivot quickly. I can still use my current flour and eggs, even if I need to run to the store to grab raisins for my oatmeal raisin cookies.

As much as the space folks expect to see reductions in cost, schedule, and implementation of rapid substitutions, the material handling industry can achieve the same thing in material handling system deployment, using the SOFTBOT Platform.

Lest you think the analogy is not applicable (rocket science vs. dirty warehouses), I would remind you that we material handling industry practitioners can get un-bruised avocados around the world, daily, for morning toast. Yet, it takes those slackers in the space industry months to get even a single payload to Mars.